You might also like:

There were 5000-square-metre plots of Chiloe for sale in the Wall Street Journal the day I arrived on the island.

No-one was revealing the price; but according to locals, and assuming they weren’t telling porkies, they were likely to cost three times more than they did this time last year.

I tried to imagine Wall Street types creating their second life here among farmers and fishermen who believe that a goblin called Trauco attracts single women into the forest and impregnates them (thus explaining any unwanted pregnancy on Chiloe); or that a ghost ship called El Caleuche sails off the coast of Chiloe, kidnapping men then returning them next morning (thus explaining why a man might not have made it home to his wife at night).

Someone’s selling bite-sized chunks of Chiloe to burnt-out billionaires looking for a quiet life, but I wonder if Wall Street knows Chiloe is one of the Southern Hemisphere’s most mysterious pockets, populated by people who live by myths and legends.

Have you even heard of it? All but a handful of Australasian travellers rush right past it in their dash to Torres Del Paine National Park from Chile’s capital, Santiago. Perhaps that’s because Chiloe’s not actually part of the Chilean mainland and until recently there was no way to get there except by boat … and that’s how the locals preferred it.

I get to Chiloe in under 90 minutes from Santiago. Locals have been fighting a bridge connecting it to the mainland for 47 years, but someone built an airport. There’s little written about Chile’s second-largest island in Australasian publications, but I know Charles Darwin was so fascinated by it that he wrote an entire book about it; and that Chilotes are so fiercely independent they resisted joining the newly independent Chile for eight years.

Life looks decidedly agricultural here; a farmer shepherds a small flock of sheep across a dirt road in front of me. The island is a patchwork of green and calico pastures, and potato plantations, flanked by the Andes and an archipelago of 40-or-so islands in the Sea Of Chiloe. My hotel, Tierra Chiloe, is built on a slope where horses feed, above a bay. When the tide runs out, locals gather seaweed to sell at market; when it’s up, fishermen launch old wooden boats. I’m one of nine guests at the 24-room hotel.

Tourism numbers are increasing on Chiloe. Many come for its 16 World Heritage-listed wooden churches, particularly through the warmer summer months, but guide Javier Mozo tells me we won’t see another tourist wherever we choose to go.

“In Torres Del Paine [national park], there are always crowds,” he says. “In Chiloe, there are always sheep.”

He tells me nowhere is as lonely as Chiloe’s Pacific Coast: a place of near-impassable Valdivian rainforest, buffeted by the gigantic waves of the Southern Ocean, where cattle trails take hikers through farms and along coastline from which souls leap from in their journey to the next world.

We leave next morning, driving across green valleys where sheep graze. We hit the coast, where the air’s thick with salt spray. The road ends where the tide rushes into a pretty bay. Thorns scratch at my face as I mistime my walk across a black-sand beach; Darwin warned of the dangers here: “… As for the woods,” he wrote. “I shall never forget or forgive them; my face, hands and shinbones all bear witness to what maltreatment I have received in simply trying to penetrate into their forbidden recesses.”

As I climb to my first viewpoint, I watch gigantic waves crash on pulverised sea stacks, squeezing through sea caves created by million of years of abuse. Beyond the whitewash, sea lions and otters swim. We’re high up on sea cliffs here, staring down across a coastline as arresting as Kauai’s world-famous Napoli Coast. But here, there’s no-one.

“I’ve never seen another hiker on this trail,” Mozo says, “Just locals on horses who come to pick seaweed.” We trudge through one of the world’s only temperate rainforests, green with 15 types of endemic fern, populated by animals named by Darwin. I shelter in here when it rains; this is one of the world’s wettest places and “… nothing but an amphibious animal could tolerate the climate”, Darwin wrote. It’s slippery as I skate down narrow ravines between seaside mountains in gumboots. It’s with relief that I reach the black sand of a tiny bay, where wild waves run right to my feet, and the skeletons of old wooden boats lie rotting in the dunes as eagles and turkey vultures circle above.

A salty sea dog called Alfonso picks us up in a motor boat where the river meets the beach at Chepu, transporting us past a wooden wharf built on top of the cliffs to the south (called The Wharf Of Souls, it’s where the departed sail for their next voyage). I ask Mozo if Alfonso believes in El Caleuche, and Trauco, and witches and goblins. Mozo translates: “He says, ‘of course he does’.”

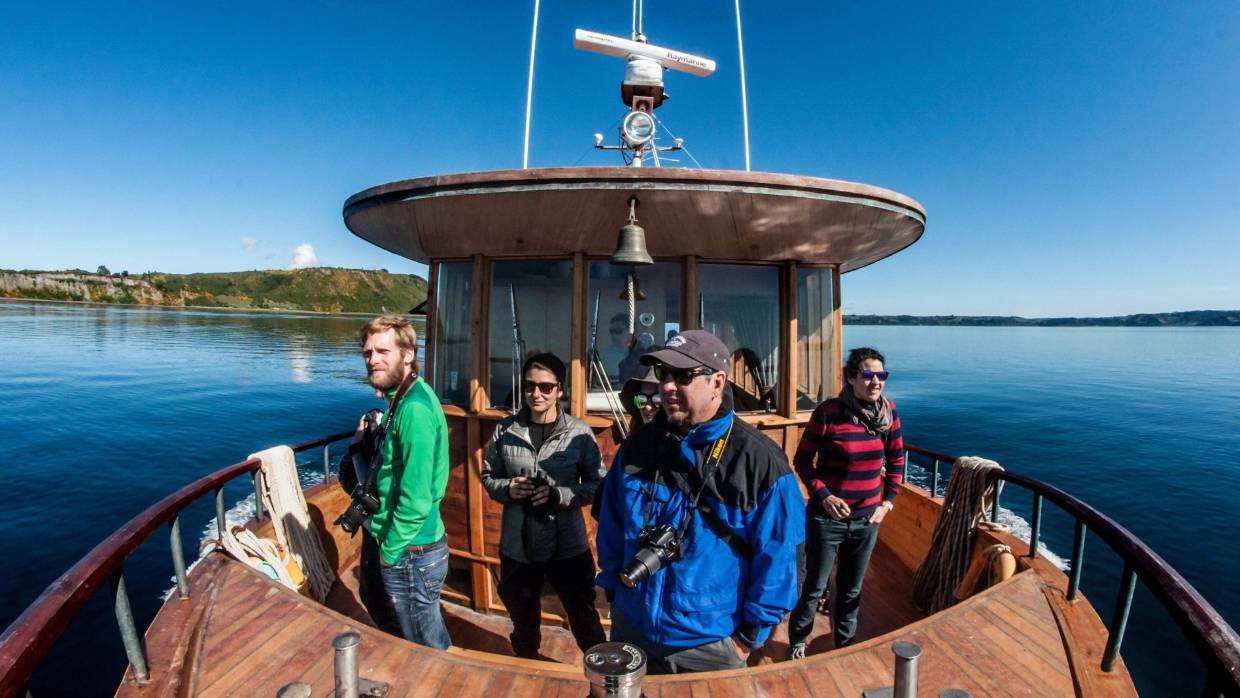

Chiloe’s east coast is the calm to the west coast’s storm. It’s where Darwin preferred to linger, near an inland sea of islands where Chilotes have lived, mostly at peace, for millennia. Tierra Chiloe looks out across these islands – and so they’re easy to access with the hotel’s old timber cruiser, Williche. We steam off with Austral dolphins surfing the bow waves, orca occasionally come here to feed, while pygmy blue whales linger in narrow fiords between islands. We pass fleets of bright-coloured fishing boats and anchor off islands that are home to tiny communities of farming families. On Chelin, we climb the bell tower of the tiny village’s 17th-century Jesuit church, careful not to sound the bells that call the 150-or-so villagers to meetings. The ceilings of these World-Heritage-listed churches are built like upside-down boats, because the best carpenters in town were always the boat builders. Locals tend to plots of potatoes and corral sheep between pastures.

Other islands I can reach by car ferries that carry just a handful of cars. Despite the reputation Chilotes have for introversion, I’m invited into their farms for meals, such as Curanto – a feast of chicken, mussels, potato, clams and fish cooked over hot rocks in a pit dug in the dirt. On horse rides, I meander through tiny villages where children rush from school yards to greet me. My presence feels like a novelty: for five days I see almost no other travellers. Instead, on excursions I connect with communities of farmers and fishermen, gaining insight into their superstitions and the hold they have over their lives (every fishing day, for instance, is dictated by the mood of the spirit La Pincoya who determines if the fish will bite). In cities such as Castro, I feel invisible as I watch life play out around me in bustling fish markets and on narrow streets beside the colourful palafito stilt houses which line the water.

In some towns, such as Dalcahue, I see new B&Bs and cafes and restaurants; and tourists in the streets. But Chiloe – for now, at least – allows travellers an insight into an ancient place ruled by millennia-old myths and the traditions of its indigenous Mapuche people. Tourism has a habit of making destinations comply with the sensibilities of our modern world, but on Chiloe, it’s still okay to believe in things that can’t be Googled.

TRIP NOTES

FLY

LATAM operates four flights a week from Auckland to Santiago. See latam.com

STAY

Rooms at Tierra Chiloe cost about $US750 (NZ$1172) per person, including transfers, daily excursions and all meals and beverages (including alcohol). See tierrahotels.com/chiloe

CARBON FOOTPRINT

Flying generates carbon emissions. A return trip for one passenger in economy class flying from Auckland to Santiago would generate 3.6 tonnes of CO2. To offset your carbon emissions head to airnewzealand.co.nz/sustainability-customer-carbon-offset

Craig Tansley was a guest of Tierra Hotels.

FIVE MORE SECRET SOUTH AMERICAN DESTINATIONS

COLOMBIA’S COFFEE TRIANGLE

Colombia’s version of Switzerland, fly to Pereira from Bogota and go hiking, hot-air ballooning and coffee tasting.

SAN MARTIN DE LOS ANDES, ARGENTINA

Tourists flock to Bariloche 200 kilometres south, but San Martin offers world’s-best fly-fishing and estancia stays with gauchos.

BONITA, BRAZIL

Few have heard of this coastal town near Bolivia’s border, but here rivers run through virgin rainforest and the diving is Brazil’s best.

HUACACHINA, PERU

Like a mirage in the desert, Huacachina is surrounded by sand dunes beside a lake ringed by palm trees in Peru’s south-western corner.

BOLIVIA’S AMAZON

Escape the crowds elsewhere in the Amazon with a 35-minute flight from La Paz to Rurrenbaque where river boats take you into jungle.

Source: stuff.co.nz