You might also like:

Imagine you’re waiting at the gate 45 minutes before departure — in spite of the fact that your jet hasn’t even pulled up yet — and you notice your pilots talking to the customer service agent. Depending on where they are in their day or trip, they may look well rested with crisply starched shirts, or they may look like you feel after hustling to make your second connection of an itinerary.

Meeting the Crew

Getting ready for the first flight of any trip begins in the briefing room. Every airline has hubs where a majority of the airline’s flights begin and end — those hubs are generally where the flight crews are based as well. The crew begins their day by meeting in operations 60-90 minutes before departure. Because these pilot domiciles are so large, there’s a good chance that I have never flown with that particular crew before, so after a few preliminary introductions and some small talk, we’ll start going over the paperwork for our upcoming flight.

Checking the Plane for Potential Problems

The first thing I look at is the maintenance status of the aircraft. The paperwork includes the current write-ups and any inoperative aircraft components — as I discussed in one of my earlier posts, there are occasions when some non-essential aircraft systems may not be at 100%, but the plane is still safe to fly.

In addition to the current aircraft status, I also review the plane’s maintenance history, which highlights systems that have had to be repaired, as well as any corrective actions on those items and issues that have had more than one write-up. This history is important because if something unusual happens at the gate or during the flight, this knowledge will help the crew troubleshoot the problem.

Watching the Weather

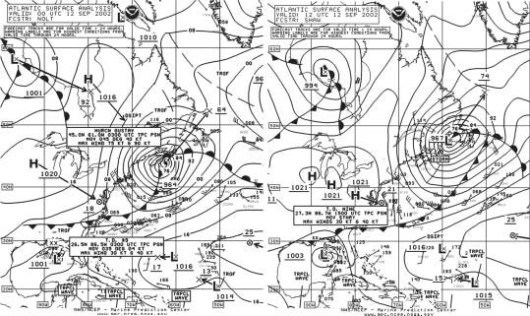

Next, I take a look at what the weather will be like from the time we leave to when we arrive. For departure, I focus on any low-altitude weather in the vicinity of the airport.

Each season has its own set of challenges. In the winter, I have to consider the precipitation falling at the airport to determine if we’ll need to de-ice, the condition of the runway to calculate if we need to take precautions for less-than-ideal braking in the event of an aborted takeoff, icing conditions in the clouds and takeoff delays that may require extra fuel. In the summer, I have to look for thunderstorms and the wind shear that accompanies them. During the spring and fall, I have to keep an eye on all of these factors, depending on the day.

I also focus on high-altitude weather systems, the location of the jet stream and high-altitude wind patterns. Reviewing pilot reports on turbulence along our planned route also helps. Sometimes the dispatcher and I will adjust our flight path to avoid known areas of turbulence, even if it costs a little more fuel or adds a few minutes to the flight. I review airports along our route for suitability just in case I need to divert the plane for any reason.

Finally, I go over the forecasted weather at our final destination. The FAA has weather requirements for your destination that, if not met, will require the dispatcher to add enough fuel to get to an alternate destination. Basically, for an hour before to an hour after your scheduled arrival, the weather where you’re flying has to have clouds no lower than 3,000 feet above the surface and visibility greater than three miles. If an additional destination is required, we’ll try to find an airport close by. There are other events that may require additional fuel on the flight, too, like arriving in the New York area during peak travel times, if there’s thunderstorm activity at your arrival time and other oddities (like the President arriving at your destination), which will require air traffic controllers to close the airport temporarily.

Reviewing the Flight Plan

Next, I check the planned route and altitude for areas where we might expect turbulence or wind shifts, as well as keeping an eye on temperature changes over small distances that might indicate areas where unforecasted turbulence might be expected. I make sure the fuel load makes sense for the flight and ensure we have enough reserve fuel just in case. Flying out of Hawaii during peak times, for instance, may mean you won’t get your requested altitude right off the bat — as a result, you have to carry a little extra fuel to account for the higher fuel burn at a lower altitude.

I will also look at the passenger load. If there’s a possibility we may have to leave passengers or cargo behind due to our takeoff or landing weight being above the limit, I will either remove excess fuel or plan a higher fuel burn to get us back under landing weight. I also check alternate airports to make sure they’re correct on the flight plan and to make sure the weather forecast at those airports looks good. Once I’m happy with the flight plan, maintenance, weather and contingency airports, I sign off the flight plan — then, when the crew and I are all satisfied with the plan, we sign it off with the dispatcher and head to the aircraft.

Other Pre-Flight Preparations

Once at the aircraft, each pilot starts his or her pre-flight routine. We make sure the cockpit has all the safety equipment, including a fire axe, fire extinguisher, portable breathing hood, functioning oxygen masks, smoke goggles, cockpit escape ropes for evacuation and backup medical kits. We check the cockpit door security system and entry request keypad.

We then start pre-flighting all of the aircraft’s main, backup and emergency systems for functionality, including tests and fluid level checks. It’s important to check those early so we can get maintenance working on it if an issue is found. We also confirm that the fuel load is correct and cross-check the final weight and balance against the plan.

Once all of that is done, we begin programming the Flight Management Computer (FMC). The aircraft weight and fuel load info gets put into the FMC to help calculate takeoff speeds and the most efficient cruise altitude. The FMC is also programmed with the anticipated route of flight. Previously, pilots would have to hand-load every point along the route — now, most airlines use an automated system that allows the route to be directly loaded into the FMC, which must then be verified for accuracy by the pilots.

The programming of the FMC is the most labor-intensive part of pre-flight prep and requires the highest degree of accuracy. The FMC, in conjunction with the auto-flight and navigation systems, calculates the most efficient altitudes and airspeeds to fly and allows the aircraft to precisely fly along the filed route.

After everyone has completed their normal tasks, we run through our pre-flight checklists to confirm the plane is ready to go — the total number of steps to be completed before every flight numbers in the hundreds for most commercial aircraft. In addition to all those tasks, we also serve as the main point of contact between maintenance, dispatch, flight attendants, ground service, station operations and customer service. The goal is to get everyone and everything lined up to attain that all-important on-time departure.

Bottom Line

Finally, it’s time to close the door and partake in the miracle of flight — that’s the part we all love. Getting through the administrative work is the job, flying is the profession. The fact that all pilots are taught to complete each step the same way every time is what allows two or three pilots who have never met before that day to operate the flight safely and efficiently on tens of thousands of commercial flights around the world every day. Rest assured, you’re always in good hands.

Source: thepointsguy.com