You might also like:

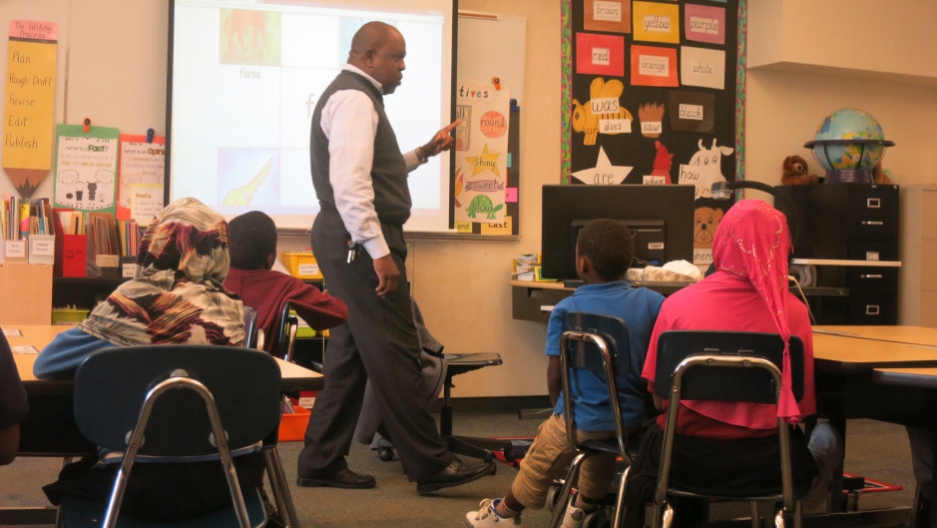

Salaad O’Barrow teaches a Somali language class at Rosa Parks Elementary School in Portland, Oregon. Stefan Fries/Oregon Public Broadcasting

That’s a challenge Portland, Oregon’s Rosa Parks Elementary School is taking up with its Somali students. It hasn’t always been easy.

In Portland, Somali students only have a 58 percent graduation rate. They also do poorly on state reading exams, and when it comes to the math tests, fewer than 10 percent pass. Those numbers persuaded Portland administrators like Michael Bacon to answer the Somali community’s call for a language program. Many of the students are refugees and struggle in English. Their parents wanted them to have the chance to also learn in their first language — like many of Portland’s Spanish speakers.

Bacon says that there are better academic outcomes when we embrace “the very assets that those children come to school with” — linguistic assets, cultural assets.

But offering a Somali-language program was a first for Oregon. To learn more, school officials traveled to Minneapolis, home to one of the largest Somali communities in the US. One person happy to see this effort was Musse Olol, with Oregon’s Somali American Council. He hoped Portland would take the Minneapolis model and run with it.

“All we needed to do was copy-paste, instead of re-inventing the wheel,” Olol says.

It’s not that simple, though.

In Portland, the Somali community is more mixed than the one in Minneapolis. Two different languages, with distinct cultural histories, are spoken here. One is Maxaa, the language of Somalia’s historic elite. The other is Maay-Maay, spoken by many Somali Bantus. Neither language was taught at any school in Oregon.

“It is important that our kids learn our language, because always it is important where you came from and who you are, and not to lose your identity,” says Portland schools aide Batula Mohamud, who is Somali Bantu.

Portland school officials spent months looking for that person who could bridge both cultures and both Somali languages — Maxaa and Maay-Maay. That person turned out to be Salaad O’Barrow. He says the two languages are similar, but different, sort of like Italian and Portuguese.

When 13 kindergarten and first graders enter O’Barrow’s classroom, he begins by chatting with them in a language many of them know from home. O’Barrow also has the Somali kids recite key syllables.

O’Barrow starts his class with the dominant language — Maxaa — because it’s easier to find Maxaa materials. He uses lots of pictures and will sometimes ask students if they know the Maay-Maay word for something.

O’Barrow agrees with many Somali parents that his students seem to learn easier by building skills in English and their native language, although his students are still young, kindergartners and first graders, so it’s still too early to see results like higher graduation rates.

But O’Barrow sees another benefit: keeping kids connected to their parents, who might only speak a Somali language. He’s seen language gaps grow at home as students immerse themselves more and more in English and lose their first language.

“Many kids they are not engaged with their parents, because of the language barrier,” O’Barrow says. “Because their parents speak Somali and they speak English, they can not communicate, even for a few minutes.”

By emphasizing two Somali languages at school, the pilot program is helping keep things equal, without leaving certain families out. Next, Portland plans to expand the program to another grade school and a high school as soon as this fall.

Source: matadornetwork.com